Near-collapse of Earth’s magnetic field 591 million years ago was a burst to evolution

The geomagnetic field around our planet is one of the reasons life on Earth exists and thrives. But around 591 million years ago, it almost vanished, an event that might have served as a catalyst for atmospheric oxygenation and diversification of organisms, according to a study published in the Communications Earth & Environment journal in May.

The findings indicate that the magnetic field's severe weakening over a 26-million-year time coincided with the Ediacaran Period. During this time, increased oxygen levels in the atmosphere and oceans supported the development of the first multicellular, oxygen-breathing organisms.

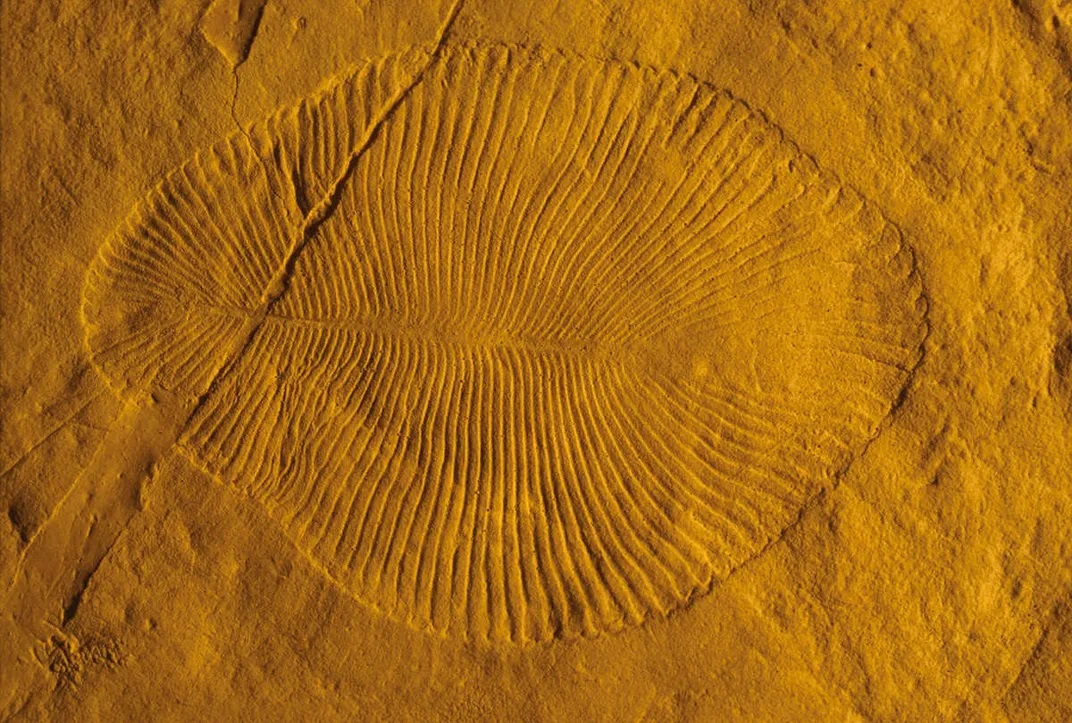

The Ediacaran fauna were unlike modern life forms, often appearing as disc-shaped entities or formless masses, some over three feet in size. These organisms, such as the blob-like Dickinsonia (pictured below), represent some of Earth's earliest known animals.

Researchers theorize that the weakened magnetic field allowed solar radiation to strip away hydrogen and other light gases from the atmosphere, resulting in a surplus of free-floating oxygen atoms available for use by emerging organisms.

"If we’re right, this is a pretty profound event in evolution," lead author John Tarduno, a geophysicist at the University of Rochester, said in an interview with Live Science.

Building on earlier research on magnetic field fluctuations, the team examined rock crystals that cooled over thousands of years, serving as time capsules of the magnetic field's strength.

Analysis of feldspar from southern Brazil showed that 591 million years ago, the magnetic field was 30 times weaker than today.

In contrast, two-billion-year-old rocks from South Africa indicated that the magnetic field then was as strong as it is now.

During this ancient period, Earth's core was liquid, the researchers explained. The heat transfer from the liquid core to the cooler mantle drove the movement of molten iron, sustaining the magnetic field. By the Ediacaran, the temperature gradient had diminished, slowing core movement and weakening the magnetic field.

More to read:

Scientists announced the start of a new epoch in Earth’s history

The study also addresses the timeline of the Earth’s core solidification, previously estimated between 2.5 billion and 500 million years ago. The new findings suggest it occurred more recently, around 565 million years ago. This solidification was critical for reinforcement of the magnetic field, which in turn protected Earth's water from solar radiation erosion.

While the consensus has been that photosynthesizing organisms like cyanobacteria produced the surplus oxygen during the Ediacaran, study co-author Shuhai Xiao, a geobiologist at Virginia Tech, notes that this new research doesn’t negate that idea.

Instead, it proposes that multiple processes, including the weakened magnetic field, contributed to oxygenation, facilitating an explosion in animal evolution.

Earth’s magnetic field is crucial for life, shielding the planet from solar winds, radiation, and extreme temperature variations.

***

NewsCafe relies in its reporting on research papers that need to be cracked down to average understanding. Some even need to be paid for. Help us pay for science reports to get more interesting stories. Use PayPal: office[at]rudeana.com or paypal.me/newscafeeu.