First complex organisms appeared 2.1 billion years ago

It was believed until now that complex life forms on our planet emerged during the Ediacaran Period around 635 million years ago but an international team of paleontologists from Cardiff University (UK), the Toulouse University (France), the Poitiers University (France), and China’s Nonferrous Metals Geology and Mining Co. Ltd has discovered evidence of a much, much earlier ecosystem in the Franceville basin near Gabon.

The scientists claim in a study published in the journal ScienceDirect/Precambrian Research that the outburst of first complex organisms took place on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa more than 1.5 billion years earlier than believed and was a result of collision of two continents - Africa and South America.

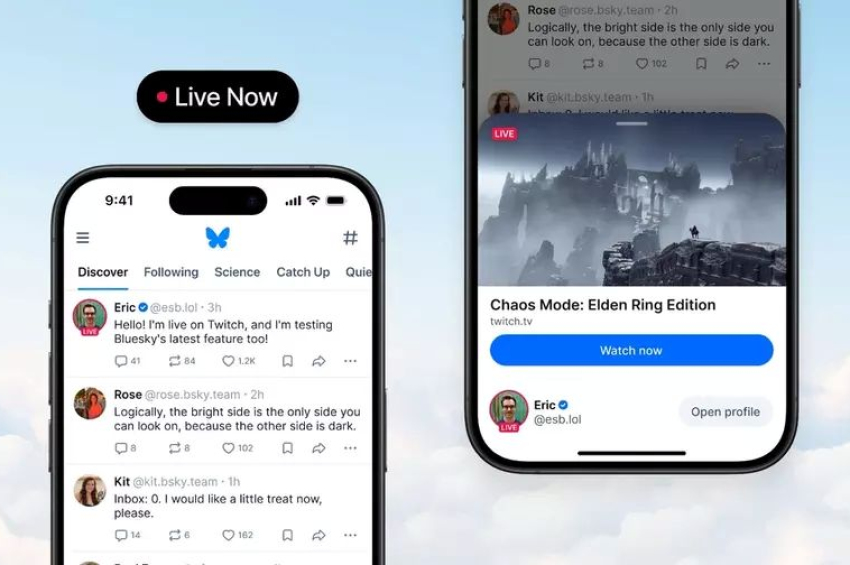

An artist’s impression of the lobate macrofossils living 2.1 billion years ago in a shallow marine inland sea created by the collision of two continents. Image: University of Poitiers

The availability of phosphorus in the environment is thought to be a key component in the evolution of life on Earth, especially in the transition from simple single cell organisms to complex organisms like animals and plants, according to Dr. Ernest Chi Fru, the team’s leader.

More to read:

[video] Los Angeles museum exhibits the world’s only green-boned dinosaur

“We already know that increases in marine phosphorus and seawater oxygen concentrations are linked to an episode of biological evolution around 635 million years ago.

Our study adds another, much earlier episode into the record, 2.1 billion years ago,” he said.

While paleontologists have long known that large-sized fossils of macroorganisms from the Ediacaran period are the earliest of the kind in geologic record, Dr. Chi Fru and his colleagues have identified a link between environmental change and nutrient enrichment before their emergence, which might have triggered their evolution.

More to read:

Scientists announced the start of a new epoch in Earth’s history

Their geochemical analysis of marine sedimentary rocks deposited 2.1 billion years ago sheds new light on the unusually large fossils in the Francevillian basin.

"We think that underwater volcanoes, which followed the collision and suturing of the Congo and São Francisco cratons into one main body, further restricted and even cut off this section of water from the global ocean, creating a nutrient-rich shallow marine inland sea," Dr. Chi Fru explained, pointing to the collision of the African and South-American continents.

This created a localized environment where cyanobacterial photosynthesis was abundant for an extended period, leading to the oxygenation of local seawater and the generation of a large food resource. This would have provided sufficient energy to promote an increase in body size and greater complexity in behavior observed in primitive, simple animal-like life forms such as those found in the fossils from this period.

More to read:

Human ancestors were almost extinct 900,000 years ago

However, the restricted nature of this water mass, along with the hostile conditions beyond its bounds for billions of years later, likely prevented these enigmatic life forms from taking a global foothold.

The study suggests that these observations may indicate a two-step evolution of complex life on Earth. The first step followed the initial major rise in atmospheric oxygen content 2.1 billion years ago, and the second followed a subsequent rise in atmospheric oxygen levels some 1.5 billion years later.

While the first attempt failed to spread, the second went on to create the animal biodiversity we see on our planet today, the team concluded. The first animals on land evolved 500 million years ago.

***

NewsCafe relies in its reporting on research papers that need to be cracked down to average understanding. Some even need to be paid for. Help us pay for science reports to get more interesting stories. Use PayPal: office[at]rudeana.com or paypal.me/newscafeeu.