A world divided by degrees: New analysis warns of growing inequality behind record education levels

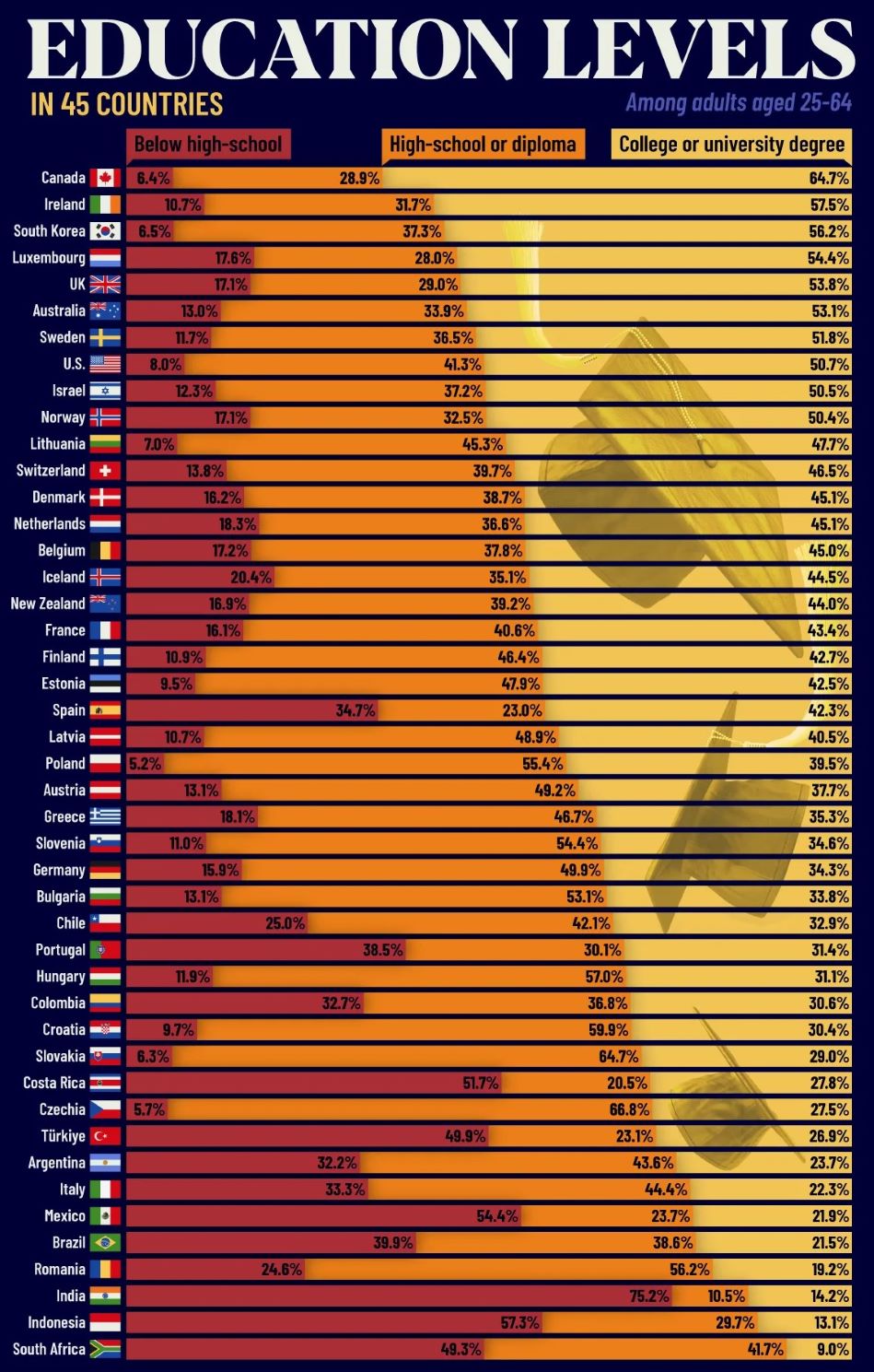

In a world where knowledge is power, Canada stands unrivaled. Nearly 65% of Canadian adults now hold a college or university degree — the highest share anywhere on Earth, according to the OECD’s new Education at a Glance 2025 report that covers 45 countries.

Ireland is the second best performer with more than 57% and South Korea the third with 56% of population holding a higher education degree. In the European part of the OECD, Romania performs the worst among the surveyed nations: 19.2%.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, South Africa, Indonesia, and India tell a different story. In South Africa, just 9% of adults have completed higher education. In India, three-quarters of adults have not even finished high school.

Source: VisualCapitalist

The contrast could hardly be sharper: while Canadians graduate into high-skilled economies, millions elsewhere remain trapped by limited schooling and shrinking opportunities.

“Inequality in access to education continues to shape people’s life chances,” the report warns, calling the divide “a threat to social mobility and economic resilience.”

A record high — but progress is slowing

Globally, the share of young adults (25–34) with a tertiary qualification has climbed to 48%, an all-time high across OECD countries. Yet the boom in higher education is losing steam. Between 2000 and 2021, tertiary attainment rose roughly one percentage point per year. Since 2021, growth has slowed to just 0.3 points annually, hinting that expansion alone can no longer drive progress.

Education systems, the authors note, have reached a “turning point”: the challenge is no longer getting more students into universities — it’s ensuring they learn what truly matters.

Degrees without skills

Behind the impressive diploma numbers lies a worrying truth — many graduates struggle with basic literacy and numeracy.

Across the OECD, 61% of adults without secondary education cannot understand complex texts. Even among university graduates, 13% remain at this low proficiency level.

More to read:

Human intelligence is declining dramatically - research

In Finland and Japan, more than 80% of tertiary-educated adults reach high literacy levels (Level 3 or above). In Chile and parts of Eastern Europe, fewer than half do. Literacy scores, on average, have fallen over the past decade — especially among the least educated.

The OECD warns of “a growing disconnect between education attainment and actual skills,” underscoring that a diploma “is not always proof of proficiency.”

The rich learn more — and earn more

Social background remains the most reliable predictor of academic success. Across OECD countries, just one in four young adults from families without secondary schooling complete higher education. Among those with at least one tertiary-educated parent, that figure jumps to seven in ten.

Some countries have managed to narrow the gap. Denmark’s rate of tertiary attainment among students from disadvantaged families has surged 20 percentage points since 2012. But progress elsewhere has stalled or reversed.

More to read:

Where do people work hardest in 2025?

For those who do graduate, the payoff remains large: tertiary-educated adults earn 54% more than those with only a secondary diploma, and holders of master’s or doctoral degrees earn 83% more. Over a lifetime, the return on higher education can exceed $300,000.

Yet the OECD cautions that this reward is increasingly reserved for the privileged few able to overcome structural barriers.

A global teacher shortage deepens the divide

Adding to the crisis, many countries are struggling to recruit and retain qualified teachers. Across the OECD, 7% of secondary teachers lack full credentials, and in Denmark, Estonia, and England, up to 10% resign each year.

Some governments are opening the classroom doors to second-career professionals, hoping to plug gaps. But without better pay and conditions, education systems risk “a slow erosion of quality from within.”

More to read:

Why Danish police play video games with kids

Two worlds of learning

The report also paints a divided landscape. In Canada, Ireland, and South Korea, higher education is now a universal expectation. In India, Indonesia, and South Africa, it remains a rare privilege.

The result is a widening global fault line — between societies that thrive on innovation and those still struggling to lift their citizens out of poverty.

“Expanding access alone is no longer enough. To sustain progress, countries must ensure that learning translates into real skills — for every student, in every classroom, in every corner of the world,” the OECD concludes.

For some reason, the analysis does not cover China – the world’s biggest economy - or Russia, the biggest country, possibly because data from these regions are either unavailable or deemed unreliable.