Turbulence surges amid climate stress and busier skies

The skies are getting busier — and bumpier, according to a new report. From passenger jets to cargo freighters and military transports, turbulence incidents are rising worldwide.

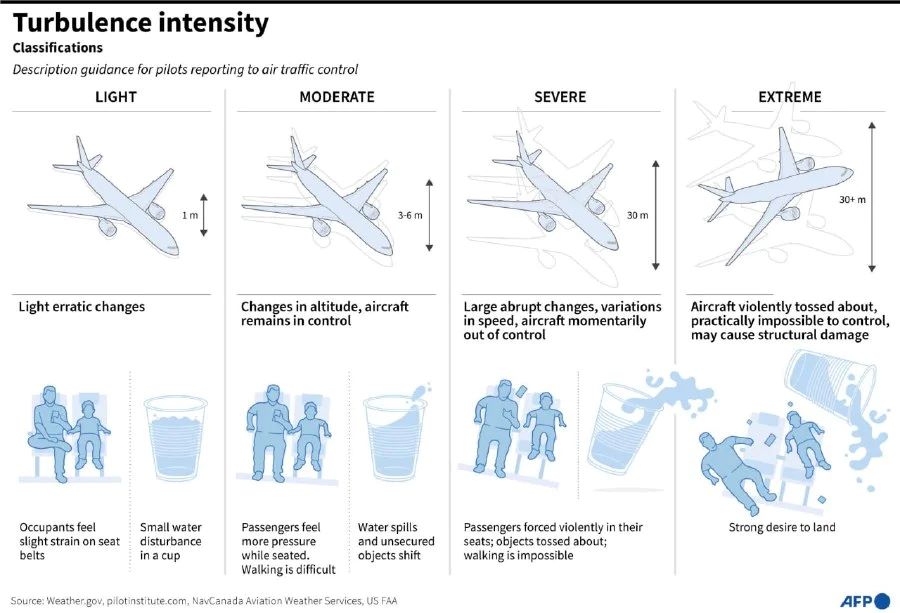

The turbulence-tracking platform Turbli ranked about 10,000 commercial routes connecting the 550 largest airports in the world using its turbulence forecast archive and evaluating turbulence along available flight tracks recorded during the year. It classified air jolts in four categories: light (0–20), moderate (20–40), strong (40–60), severe (60–80), and extreme (80–100).

Turbli found that in 2024, the most turbulent route on Earth was between Mendoza, Argentina, and Santiago, Chile, recording an average eddy dissipation rate (EDR) of 24.684. The routes between Santiago and Cordoba, Argentina, and Mendoza–Salta (Chile) ranked second and third, accounting for 20.214 and 19.825 incidents, respectively.

Aviation experts warn that a “perfect storm” of factors is reshaping flight safety: soaring global air traffic, a rapidly heating atmosphere, and increasingly powerful jet engines that push aircraft into more unstable air currents.

Mountains

The above-mentioned routes lie above the mountainous region of the Andes. In fact, mountain ranges are among the primary causes of turbulence, playing a massive role in disturbing airflow. When strong winds hit steep terrain, they’re deflected upward and downward in waves, creating violent ripples that can extend for hundreds of kilometers.

This mountain-wave turbulence is common near the Andes, Rockies, Alps, and Himalayas, often forming without clouds or visible signs. Even modern radars struggle to detect it in advance. Pilots crossing these ranges frequently report sudden jolts or altitude drops, particularly when jet streams interact with the terrain below.

Growing number of flights

With more than 138,000 daily commercial flights as of mid-2025 — and a growing mix of passenger, cargo, and military jets — the sky is more crowded than ever. Each plane leaves behind wake vortices — mini tornados that can persist for minutes. As air corridors fill, the likelihood of one aircraft encountering another’s disturbed air increases, raising the odds of turbulence encounters.

The number of flights today dwarfs anything seen before in human history. In 2025, airlines will operate over 35 million commercial flights. A century ago, commercial aviation was barely born and aircraft were fragile, slow and short-range, rarely crossing mountains or oceans. In the 1920s, there were only a few thousand flights a year worldwide — mostly experimental or postal routes.

Faster jets, thinner margins

Modern aircraft, by contrast, are larger and heavier but fly higher and faster than ever before. These efficiencies mean less aerodynamic cushioning when turbulence strikes.

High-powered engines slicing through the upper atmosphere at 900 kilometers per hour and thinner air amplify both the sensation and structural stress of each jolt, according to aviation experts.

At 35,000 feet, a sudden vertical wind shift can impose tons of force within seconds.

And while modern composites and wing flexibility help absorb some of that energy, the combination of speed, altitude, and thinner air still leaves little margin for error when turbulence develops suddenly. Even with stronger materials and smarter wings, modern jets remain at the mercy of invisible air currents — a reminder that, above the clouds, nature still calls the shots.

Heating climate

This factor is often neglected by airlines and regulators alike, but the truth is that a warming planet is destabilizing the atmosphere. As temperature gradients intensify, jet streams shift and clear-air turbulence zones expand. Climate change amplifies temperature contrasts in the upper atmosphere, making wind speeds more volatile and increasing the frequency of clear-air turbulence at cruising altitudes.

A 2023 study found that severe clear-air turbulence over the North Atlantic — one of the planet’s busiest flight routes — was 55% more frequent in 2020 than in 1979.

Another research suggests moderate-to-severe turbulence could increase by up to 150% this century as greenhouse gas concentrations rise.

Troubling statistics

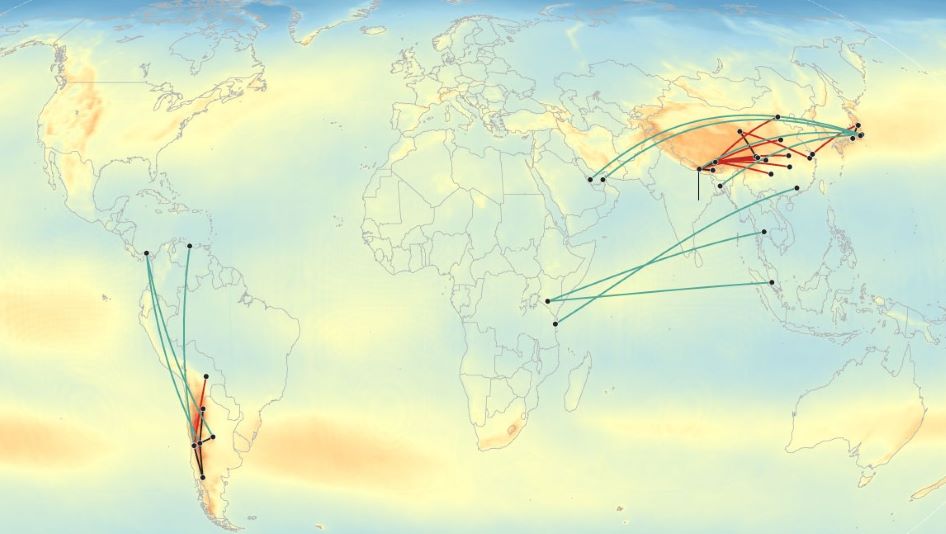

The Turbli report says South America’s Andes and Asia’s Himalayan regions were the most dangerous for flying, dominating all top ten positions in the turbulence chart. By continent, the routes Albuquerque–Denver, Denver–Jackson, Jackson–Salt Lake City, and Denver–Salt Lake City were the most turbulent in North America last year.

In Europe, the riskiest routes were Nice–Geneva, Nice–Zurich, Milan–Zurich, Ferno–Lyon, Nice–Basel, and Geneva–Zurich.

Kathmandu–Lhasa and Chengdu–Lhasa experienced most turbulence incidents in Asia, while Durban–Johannesburg and Cape Town–Durban topped the chart for African flights in 2024.

A map of most turbulent routes. Credit: CNN

Soaring costs

Aside from psychological nightmare and injuries, turbulence can be a cause of death. A 73-year-old man died of a heart attack during severe turbulence on a flight from London to Singapore last year. The jet had hit violent turbulence, flinging passengers into the ceiling and service carts across the cabin.

While most turbulence incidents cause only minor discomfort, severe events are becoming more frequent, disruptive, and costly. Injuries to passengers and crew, emergency landings, and delayed schedules are all increasing. Aircraft also face greater structural fatigue from repeated stress, adding costs for maintenance, insurance, and delays.

More to read:

Stellantis will finance production of Archer Aviation

Some regulators are taking notice. Singapore’s Civil Aviation Authority, for example, has designated severe turbulence as a “major in-flight threat,” on par with mid-air collisions. This classification prompts pilots to consider emergency landings to provide medical care and inspect the aircraft. Whether others will follow suit remains to be seen.

However, airlines do react to turbulence risks. They now integrate real-time meteorological and turbulence data into flight planning systems, dynamically adjusting flight paths — but that alone is not enough.

Augmented reality

Since global air traffic is projected to keep growing by 3–4% annually, airlines can’t realistically reduce flight volumes to avoid turbulence. Instead, they’re being forced to adapt — technologically, operationally, and strategically — to a permanently more turbulent atmosphere.

This means equipping modern planes with advanced turbulence-detection systems that combine onboard sensors, LIDAR, satellite data, and AI. For example, IATA’s Turbulence Aware platform, which crowdsources real-time turbulence data from participating airlines, and Honeywell’s IntuVue RDR-4000 radar, which can detect turbulence up to 60 kilometers ahead, allow pilots and dispatchers to reroute or change altitude before entering unstable air — reducing both injury risk and maintenance costs.

More to read:

Russia suspected of taking down Azerbaijani passenger plane, mistaking it for a Ukrainian drone

It also means strengthening aircraft design to make jets more resilient to turbulence: flexible composite wings that can flex and absorb shock loads more efficiently; lighter materials that reduce stress on the airframe; and improved cabin layouts that minimize injury risks.

And finally, future aircraft — especially electric or hybrid designs — may use active wing morphing or gust load alleviation systems to automatically compensate for sudden wind changes. Pilots could rely on real-time video imaging of air waves and turbulence fields, captured by forward-facing sensors and visualized directly in cockpit displays.

These systems would allow crews to “see” invisible air currents ahead — the atmospheric equivalent of night vision — and make split-second decisions to adjust altitude, speed, or flight path long before turbulence hits.

In essence, tomorrow’s flight decks may blend meteorology and augmented reality, turning pilots into weather navigators as much as aviators.