Andromeda’s satellite galaxies are strangely pointed at Milky Way

Astronomers have spotted something puzzling about our closest galactic neighbor, the Andromeda galaxy (M31). A new study published in Nature Astronomy reveals that most of Andromeda’s smaller satellite galaxies aren’t scattered randomly, as expected, but are instead bunched up on one side — and they’re all pointing toward us in the Milky Way.

Simulations suggest the odds of this happening are less than half a percent, making the finding a big challenge to current theories of how galaxies form.

More to read:

Astronomers discover dwarf galaxy in the Milky Way neighborhood

“M31 is the only system that we know of that demonstrates such an extreme degree of asymmetry,” lead author Kosuke Jamie Kanehisa of the Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam in Germany told Space.com.

Astronomers believe that large galaxies form when smaller ones merge together, guided by “haloes” of dark matter, the mysterious substance that makes up most of the universe’s mass. This process is thought to be messy, leaving dwarf galaxies orbiting in random positions.

But Andromeda, which is expected to collide with the Milky Way in 4 to 5 billion years, doesn’t fit that picture.

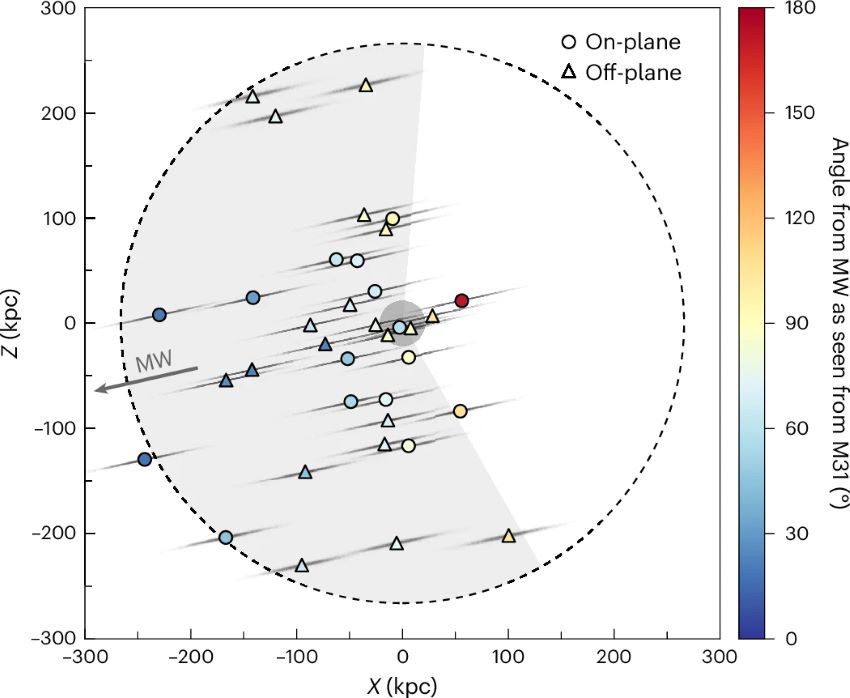

A side-on view of Andromeda’s asymmetrical satellite distribution. Credit: Nature Astronomy

Of Andromeda’s 37 known satellite galaxies, all but one are within 107 degrees of the line pointing directly at the Milky Way. Even stranger, about half of them orbit in the same flat plane — similar to how planets circle the Sun.

When researchers compared observations of Andromeda with computer simulations of galaxy formation, fewer than 0.3% of simulated galaxies showed this kind of imbalance, and only one case came close to being as extreme.

One possibility is that astronomers are simply missing a large number of faint dwarf galaxies around Andromeda, making the current data incomplete. Another idea is that Andromeda’s unusual setup is the result of its past.

More to read:

Forget what you know about cosmos – astronomers find a galaxy without stars

“The fact that we see M31’s satellites in this unstable configuration today — which is strange, to say the least — may point towards many having fallen in recently,” Kanehisa said. “Possibly related to the major merger thought to have been experienced by Andromeda around two to three billion years ago.”

The findings could even mean that the standard cosmological model itself needs adjusting. Because satellite galaxies are hard to study — they are faint and often lost in the glow of their larger host galaxies — it’s possible that Andromeda isn’t so unique after all.

To prove one or another point in galaxy formation theories, astronomers have to gather more data — not just on Andromeda’s satellites, but on those of other, more distant galaxies too.

More to read:

Astronomers capture images of a different kind of galaxy

The Milky Way and Andromeda are moving toward each other at roughly 110 km per second (about 250,000 mph). When they eventually meet, they won’t crash like solid objects — instead, their stars and gas clouds will be pulled around by gravity, forming a new giant elliptical galaxy often nicknamed “Milkomeda.”

Even though it sounds dramatic, scientists believe that the chance of our Sun or Earth actually colliding with another star is extremely small because stars are so far apart. However, the night sky will look very different: in a few billion years, Andromeda will loom larger and brighter until the galaxies finally merge.

Andromeda’s satellite galaxies will most probably part of the new super galaxy.

![[video] Navalny team released photographs of another “Putin palace” — in Crimea](/news_img/2025/12/30/news1_mediu.jpg)