Infant universe was abundant in black holes

Supermassive black holes are among the most fascinating and intimidating objects in the universe, with masses reaching a billion times that of the Sun. Scientists have long known they’ve existed since the universe's infancy but whether there were more or less than now – this remained a puzzle, until recently.

Looking for answers to this question, astronomers focused on the observation of quasars — extremely luminous, compact objects powered by rapidly growing supermassive black holes — which date back to a time when the universe was less than a billion years old, corroborating the findings with the snapshots offered by the Hubble Space Telescope.

More to read:

[video] Astronomers discover closest massive black hole to Earth

The findings, published in a new study in the Astrophysical Journal Letters, suggest that there were significantly more (but less luminous) black holes in the early universe than previously estimated. This discovery sheds light on how these black holes formed and why many are more massive than expected.

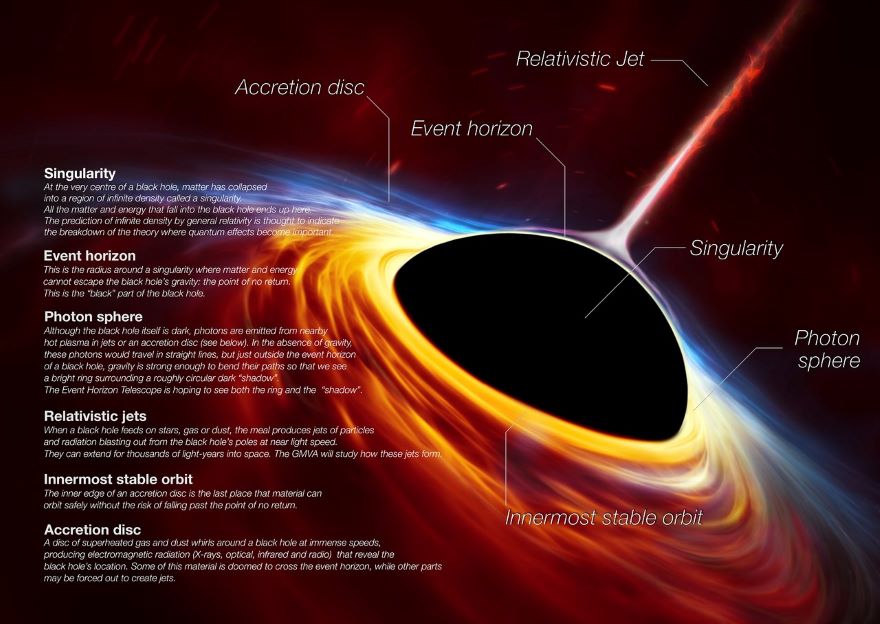

Black holes grow by consuming surrounding material in a process called accretion, which generates immense radiation. This radiation exerts pressure that limits the rate at which black holes can grow. The existence of massive quasars in the early universe presents a challenge: with so little time to feed, these black holes must have either grown faster than physically plausible or started off unexpectedly massive.

How do black holes form in the first place? Several possibilities exist:

1. Primordial Black Holes: These may have formed shortly after the Big Bang. However, while plausible for low-mass black holes, this theory doesn’t account for the significant number of massive black holes observed.

2. Stellar Mass Seeds: Black holes can form from the collapse of massive stars at the end of their lives.