Russia sets out a global nuclear trap

Despite war, sanctions, and growing geopolitical isolation, Russia’s state nuclear energy corporation, Rosatom, has emerged stronger than ever on the global stage.

Not only has it weathered the storm of Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine — it has expanded its reach, quietly embedding Russia into the critical infrastructure of dozens of countries. The strategy: long-term nuclear partnerships that bind governments to Moscow through technology, financing, and fuel, according to a new investigation.

When Russian tanks crossed into Ukraine in February 2022, many expected a mass exodus from Kremlin-linked business ventures. Instead, Rosatom’s international client base held firm, says the independent outlet Novaya Gazeta. Half of the company’s top partners — countries like India, China, Iran, and Bangladesh — refused to condemn the invasion at the United Nations, reflecting their continued comfort in working with Moscow.

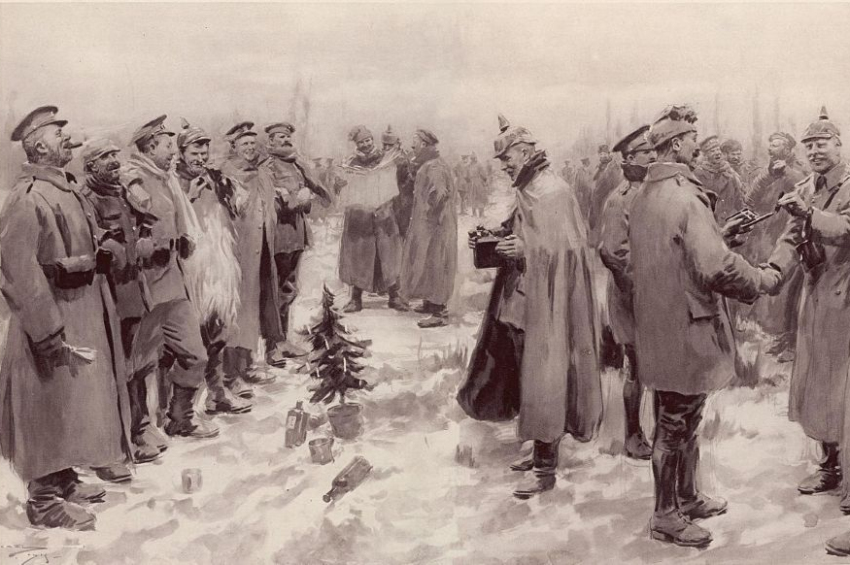

.jpg)

A sample of the first Soviet atomic bomb, on display at Rosatom. Credit: Novaya Gazeta

Even Türkiye, a NATO member, has maintained and deepened its cooperation with Russia on the Akkuyu nuclear plant, despite international tensions. “Türkiye plays a double game,” says energy researcher Téva Meyer. “It’s in NATO, but remains very close to Moscow—buying weapons, trading oil and gas, and now deepening its nuclear ties.”

Instead of shrinking, Rosatom’s foreign revenues have surged: from $9 billion before the war to $18 billion in 2024. According to analysts speaking to the outlet, Rosatom is the world’s most active nuclear builder and the war hasn’t changed that — except that it’s now almost entirely shut out of Europe.

Hungary: Europe’s exception

The sole exception is Hungary, where Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has pressed ahead with the Paks-II nuclear plant, financed largely by a €10 billion Russian loan. Despite E.U. concerns, construction is set to begin in summer 2025, and experts warn that backing out after that point will become politically and financially irreversible.

More to read:

Massive document leak exposes Russia’s giant nuclear modernization effort

Hungary’s dependence on Russia goes beyond politics. The country’s only nuclear plant was built by Soviet engineers, runs on Russian reactors, and has long sourced all its fuel from Russia.

While alternatives now exist, Budapest appears ready to double down with Paks-II, extending its dependency for decades.

Training engineers in Russian technology and relying on Russian supply chains is simply easier for Hungary; it also means walking straight into a new cycle of reliance, the report says.

Targeting the Global South

Russia’s nuclear push is not random — it’s a calculated geopolitical strategy. Since its fallout with the West after the 2014 annexation of Crimea, the Kremlin has focused Rosatom’s outreach on the Global South. The war in Ukraine only accelerated this trend.

From Africa to Southeast Asia, Rosatom is signing agreements, offering reactor construction, fuel supply, and financing — sometimes with little expectation of immediate returns. In Africa alone, Russia has inked cooperation deals with Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Zimbabwe, and Burkina Faso, among others.

The building site of the Akkuyu nuclear plant in Türkiye.

These deals serve a dual purpose. They flatter authoritarian regimes, signaling that Russia sees them as equals — and they create long-term dependencies through infrastructure and credit.

For example, in Bolivia, Rosatom isn’t just building a research reactor — it’s also negotiating lithium mining rights. In Burkina Faso, nuclear cooperation goes hand-in-hand with gold extraction deals. In Türkiye, beyond the Akkuyu reactors, Rosatom is building and controlling a strategic cargo terminal — a port facility that could have military implications in a NATO country.

A Geopolitical tool disguised as energy cooperation

Experts warn that Russia’s nuclear diplomacy is less about energy and more about influence. The model — build, own, and operate — locks client countries into decades-long relationships, with fuel, spare parts, and even training tied to Russian supply.

“The goal isn’t just cooperation, it’s dependency,” says nuclear expert Dmitry Gorchakov. “These countries will have no exit strategy without Russian consent.”

More to read:

Elon Musk fires nuclear specialists amid ongoing mass government purge

This strategy is most visible in Russia’s use of state loans — offering billions in financing for nuclear projects at rates developing nations find hard to resist. Once locked in, these governments are far less likely to turn against Moscow diplomatically.

“Rosatom is building a web of soft power,” Novaya Gazeta quotes energy experts as saying. “It’s a slow game, but it’s working.”

Europe looks for exit

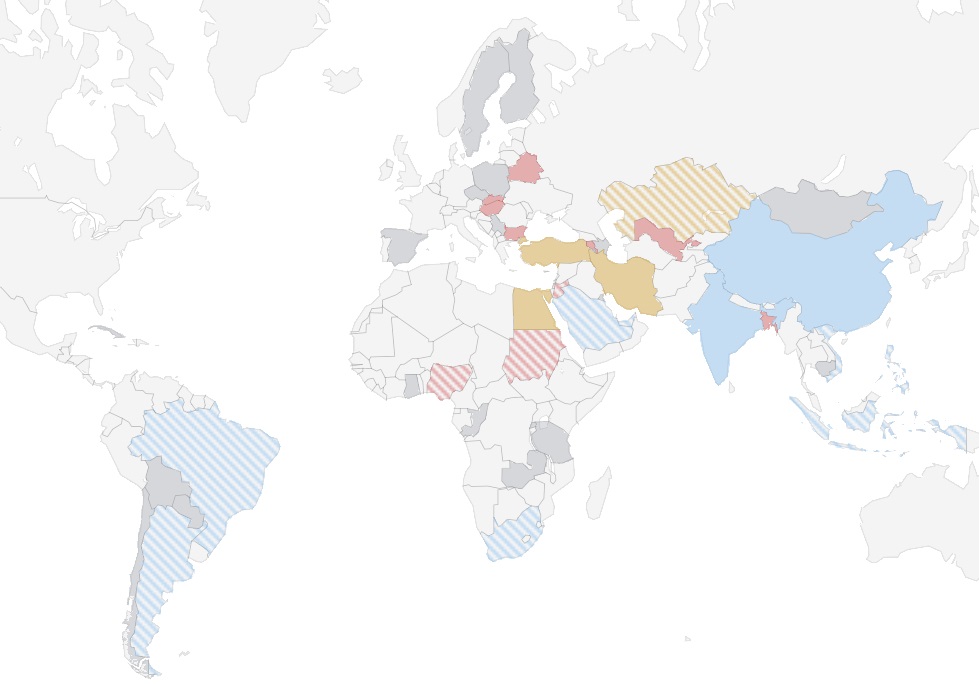

While the Global South moves closer to Russia, Europe is trying to untangle itself. For years, countries like Finland, Slovakia, Bulgaria, and Czechia relied on Russian nuclear fuel for their Soviet-designed reactors. Now they’re turning to American supplier Westinghouse, despite the higher cost and technical difficulties.

Switching suppliers, however, is a slow process—limited by production capacity and existing long-term contracts with Rosatom. Full independence from Russian nuclear fuel is expected to take at least seven years, according to E.U. estimates.

Countries with various degrees of dependency on Russian nuclear energy and expertise.

Hungary, again, remains the outlier. Even though its Paks-II plant will use next-generation Russian VVER-1200 reactors, the E.U. required that Rosatom supply fuel only for the first decade. After that, Europe hopes an alternative will exist.

A trap that works

Despite the E.U.’s efforts to reduce dependency, Rosatom remains untouched by European sanctions. That’s largely thanks to Hungary’s veto power, but also due to quiet reluctance from countries like France, which supplies turbines and control panels for Russian-built reactors.

So France benefits from Rosatom’s contracts but doesn’t want to be the one to say no to sanctions, leaving Hungary to play the bad cop while letting Paris stays clean.

More to read:

A new nuclear disaster is looming in eastern Ukraine

Even if sanctions were imposed, Rosatom is unlikely to suffer significantly. Its European fuel exports are worth just $3 billion a year, a fraction of its global business.

As the world scrambles to cut carbon emissions and shift to cleaner energy, nuclear power has regained importance. But for many developing countries, Russia is the only affordable path to atomic energy — and Moscow is using that to its advantage.

Russia is betting that once the client country is in, it stays in. That’s why Moscow offers credit, cheap fuel, and deep cooperation — because when the time comes, the client realizes it has no alternatives, the investigation concludes.